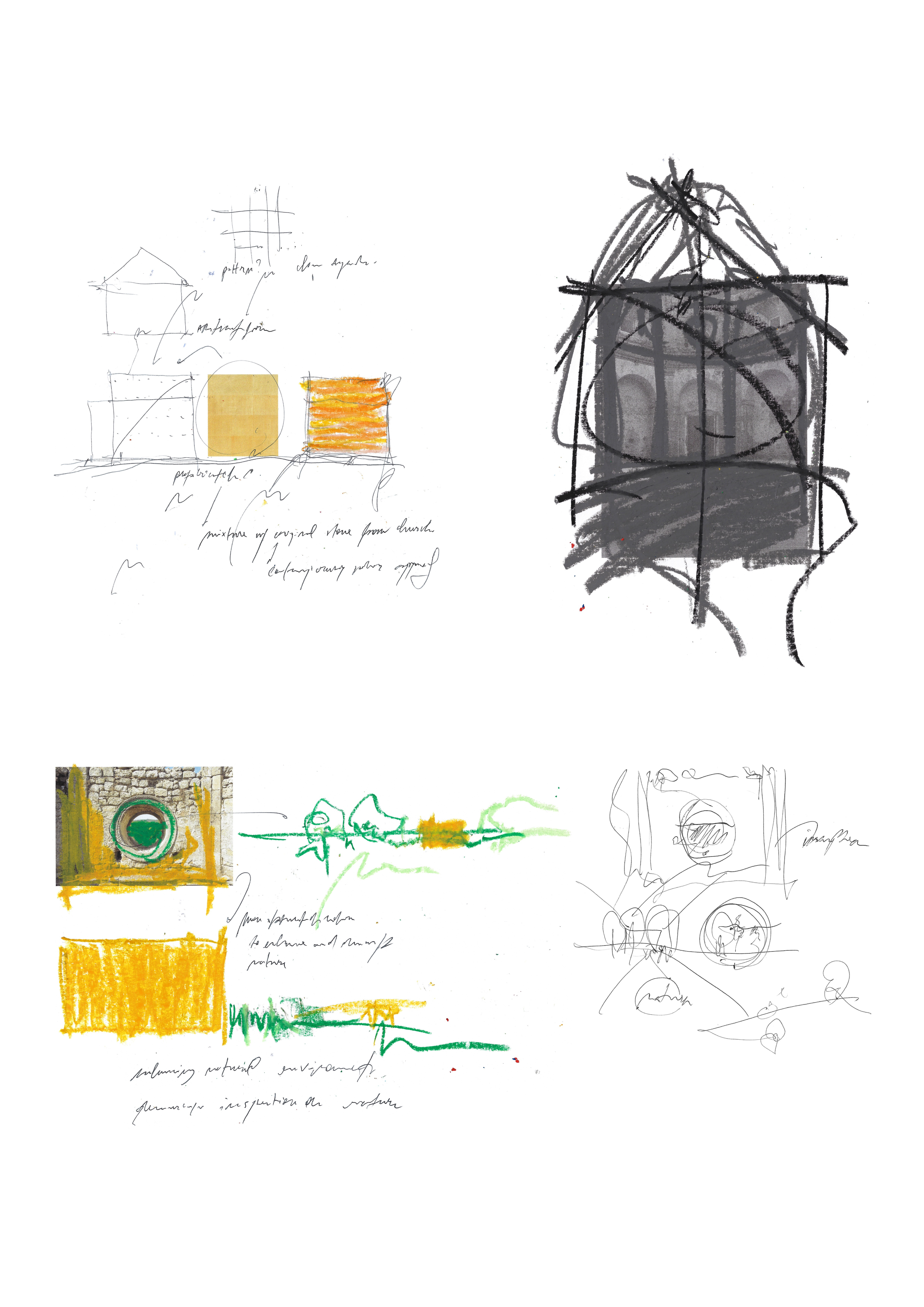

In a pivotal statement, John Berger affirmed that “drawing is discovery.”1 The act of drawing forces the author to “look at the object in front of him, to dis- sect it in his mind’s eye and put it together again.”2 Often, if not always, a drawing is the final stage of a longer process of analysis, whose elaboration it rep- resents: a synthesis, a schema. The Greek etymology of the word “scheme,” as Vittorio Ugo points out, indicates “form” in a broader sense: not exclusively a representation of the constitutive rules of an object, but also an indication of its features.3

From the Latin treatises to the Renaissance manuals, from Durand’s schematizations to Choisy’s axonometric, we can recognize several methods for coding the representation and interpretation of arch- itecture, whether built or imagined. By omitting the models of the “ideal cities” of the Renaissance (often coined as a reinterpretation of Vitruvius’s guide- lines),4 we see how these depictions pertain almost ex- clusively to constructive elements and architectural typology—neglecting the analysis of urban morphol- ogy. The city is the place represented by the painters, or the map makers. The artists have different in- struments with which to portray the city and, more- over, different aims. Instead, the representation in the cartographer’s work is triggered by a radically dif- ferent problem: the lack of technical tools able to convey the precision which is, today, requisite for any depiction of a city.

Exploring the meaning of the “scheme,” Ugo encourages us to consider a deeper meaning of the ideogram.5 More than an oversimplifying tool, it should be a reflection of the core of what it represents, a depiction of its genesis: a “theoretical drawing” able to act as a “graphical representation of a principle.”6 The Jerusalem Crusader map,7 for instance, compen- sates for its technical lack with a depiction that is not exact but “theoretical” (in this case, also symbolic and ideal), a drawing that can represent the tangible elements and the urban ordering principles of the Holy City (Fig. 1). With the Nolli Map, the depiction of the city gains unprecedented precision: Nolli includes an additional layer of meaning, choosing a specific method to represent public spaces.8 From this moment, after gaining appropriate tools to measure the city, its depiction will revolve mainly around the concept of the figure-ground plan.9

The briefly cited examples highlight how a (more or less) ideogrammatic representation can convey

the principles of a city and its urban form. Neverthe- less, the presence of color seems non-existent or irrelevant. If in the Crusader maps color has a purely ornamental function—as it does, strikingly, in the Egyptian depiction of domestic spaces and gardens— the black and white urban depictions are built on a mainly binary system. The contrast generated within these drawings renders a high level of clarity, but

the map maker has only two elements at their disposal to convey meaning: the use of black and white thus leads to a drastic reduction in the amount of informa- tion available. When enriched by nuances or hatches, the clarity is sensibly diminished: the sharpness of the drawing becomes substantially different, leading to a less direct, less immediate depiction.

The evolution of ideogrammatic representations—as well as the growth in the use of color—has been subject to broad development across the twentieth century. These explorations, nonetheless, seldom over- lapped. While certain crucial models—such as those purveyed by Oswald Ungers or Rem Koolhaas—always favored the dichromic cleanliness of white and black, color became a descriptive instrument (as in the practice of city planners)10 for precise and extensive mapping, one that is hardly ever representative of the genetic factors of urban form and its design.

It would appear, therefore, that those city de-pictions which attain such theoretical intensity often opt to erase color, which is instead used in analy- tical representations. The city, however, is a complex phenomenon: one that, if faced with only two ele- ments to represent it, could be portrayed incomplete- ly. How can that phenomenon be densified in its depiction while keeping its conceptual sharpness un- touched? How can a map preserve its clarity and, in the meantime, increase the represented elements? That’s one circumstance where the inclusion of color into the equation may (re)solve it. To explore this solution, one can take advantage of the words (and works) of the masters.

As Mark Rothko affirmed: “We favor the simple expression of the complex thought.”11 To be precise, as well as maintaining density of information, a simple expression must derive from an intentional process. A process that avoids futile elements, by carefully se- lecting only those aspects needed to convey the foun- dational contents of what we are depicting—whether that’s the city, or its architecture. Abstraction is the medium that can guide us through this route. This vehicle steering us along this arduous path is, none- theless, an unreliable one, owing to its ephemeral and non-scientific nature. The etymon of the word “ab- straction” stands, quite literally, for “dragging away.”12 Applying the concept of abstraction to a map means, after an in-depth analysis, being able to understand what elements are indispensable for representing

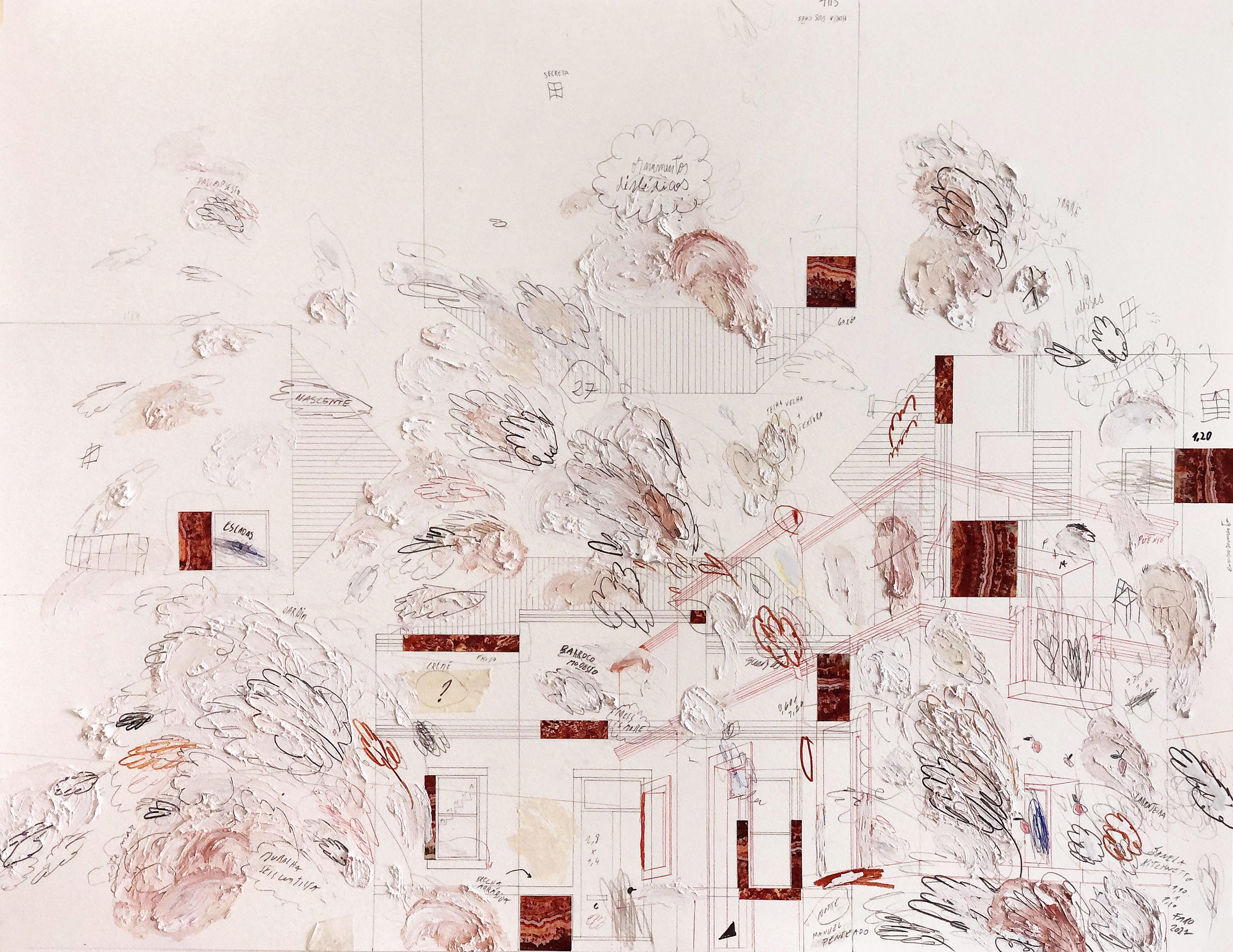

a principle—and carefully magnifying them (Fig. 2). In an operative sense, it means “leaving out” or “pulling away” unnecessary lines, surfaces, and layers from a depiction. The only elements required for an ideogrammatic representation are the ones that have a structuring role, that stand for underlying princi- ples. The ideogram, hence, has the aim of representing only the parts that conspire to define the structure of the subject.

Color, in this phase, can become an invaluable instrument. The choice of colors and the method

of their employment is the key point. As already men- tioned, the use of color increases the possibility of distinguishing different features. However, to avoid an exaggerated presence involving too many (or too many diverse) components, it is convenient to have

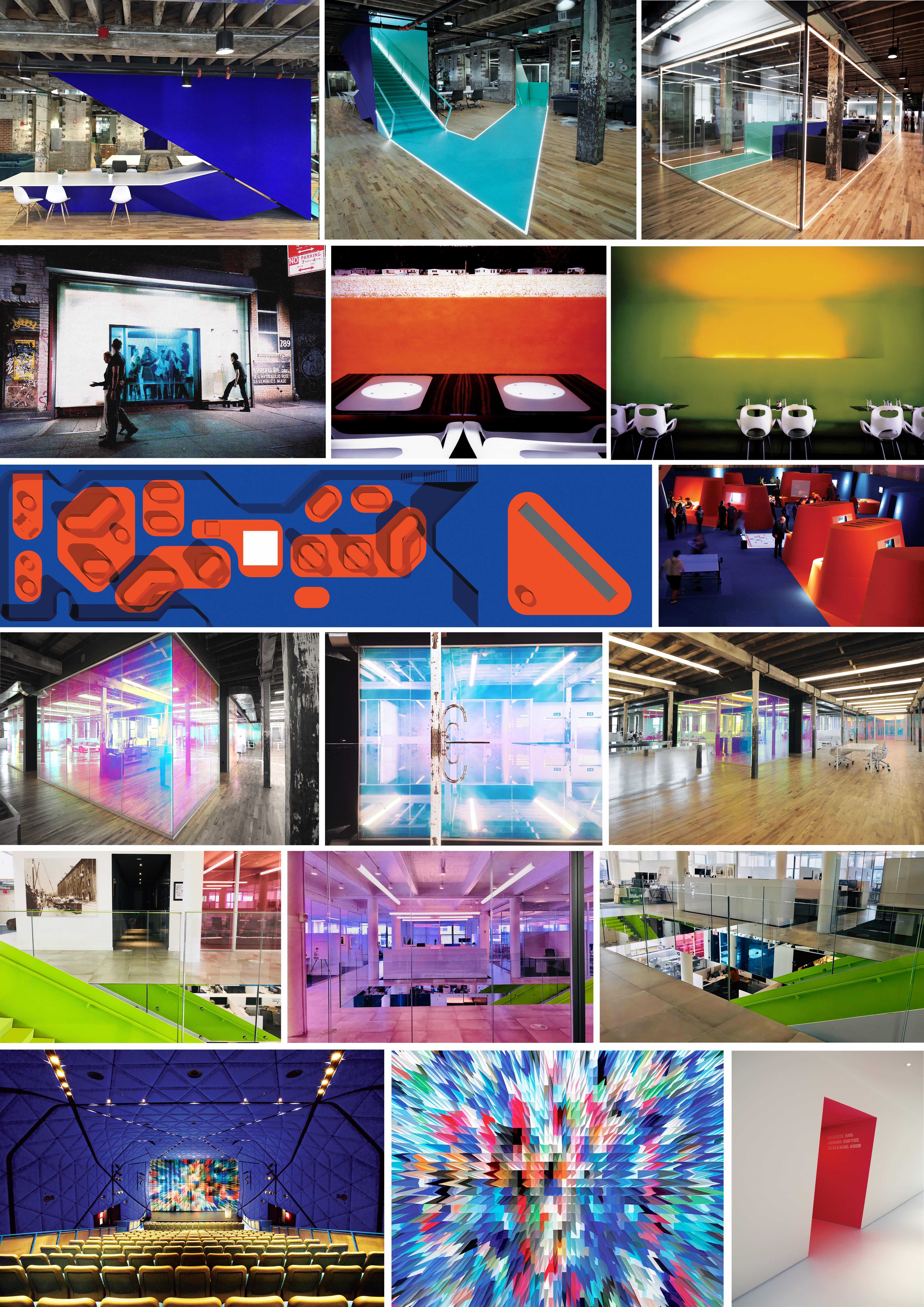

a very limited palette. It is almost inevitable that the choice falls on the primary colors and their direct descendants. Red and blue, as well as green and or- ange, are the primitive elements, immediately rec- ognizable and discernible. As Johannes Itten points out, referring to the artists of the Romantic and

the Prime Gothic era, the “harmony of pure colors” achieves incomparable “effects that are simple, per- spicuous, significant.”13 Itten stresses again—as Rothko did—the “simplicity” that is crucial to achiev- ing an effective expression.

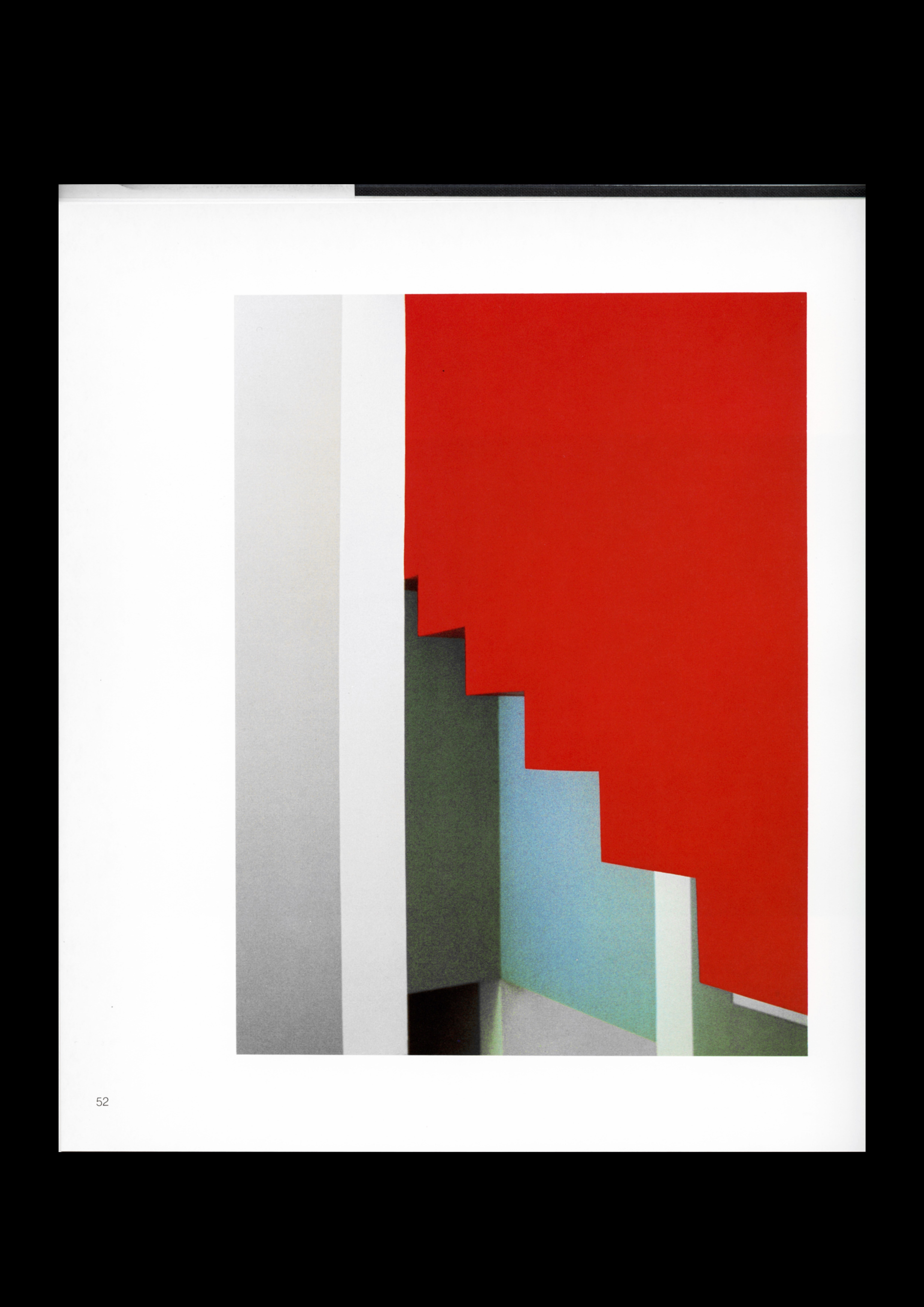

To represent architecture and urban form sys- tematically, it is necessary to keep the tone and

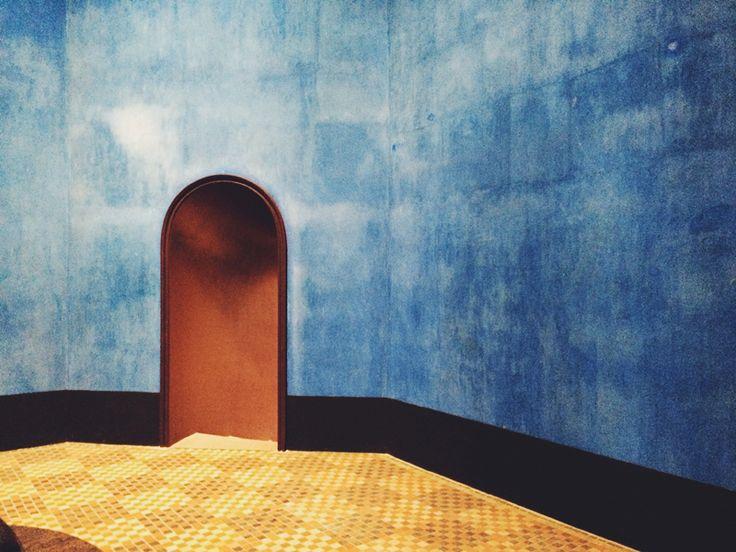

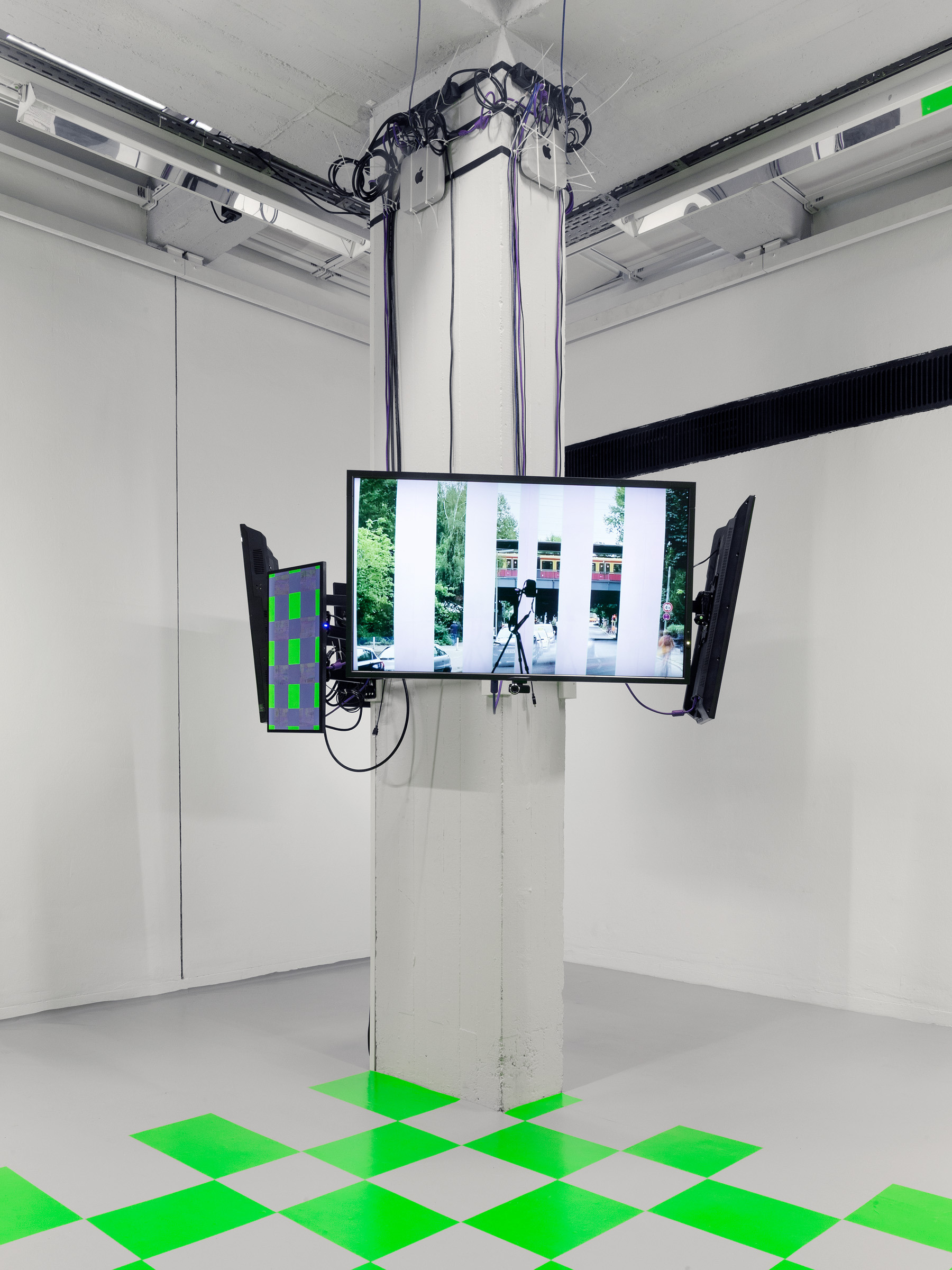

hues consistent, as well as what they stand for: in this sense, “the action of colors is to be felt and intended not only as an optical fact, but also as a ... symbolic one.”14 If neutral gray can represent a background, intended as the set of information needed to locate and represent precisely the place depicted (as it can be, for example, in the built context), red can be used to immediately recognize and stress the object of the ideogram—be it the object of the design or the analy- sis. Green and blue both possess an instinctive qual- ity that can be traced back to their abundance in the natural world. In addition to the hues, this palette can be densified by adding (or removing) brightness to the tones. Colors can be made darker to highlight them (so as, for example, when showing a stronger value) or to show differences in the volume articulation. Equally, lighter and less visible color can stand for elements that need to be represented but are less im- portant than others (Fig. 3, 4).

Color, in conclusion, can be a helpful (when not fundamental) tool. An instrument capable of pursuing different purposes but, at the same time, an instru- ment that enlarges and deepens our toolboxes when we are analyzing, representing, or reflecting on the urban framework and its architectures—already built or just imagined. Again, Itten invites us to reflect on the value of color and its instrumentality. Even if not directly concerning the representation of the city, one of his annotations referring to El Greco and Rembrandt becomes peculiarly significant here: color “disrobes his objective meaning to turn into an abstract component of the rhythm of the space.”15

Epilogue.

LOBMYS. A compositive divertissement.

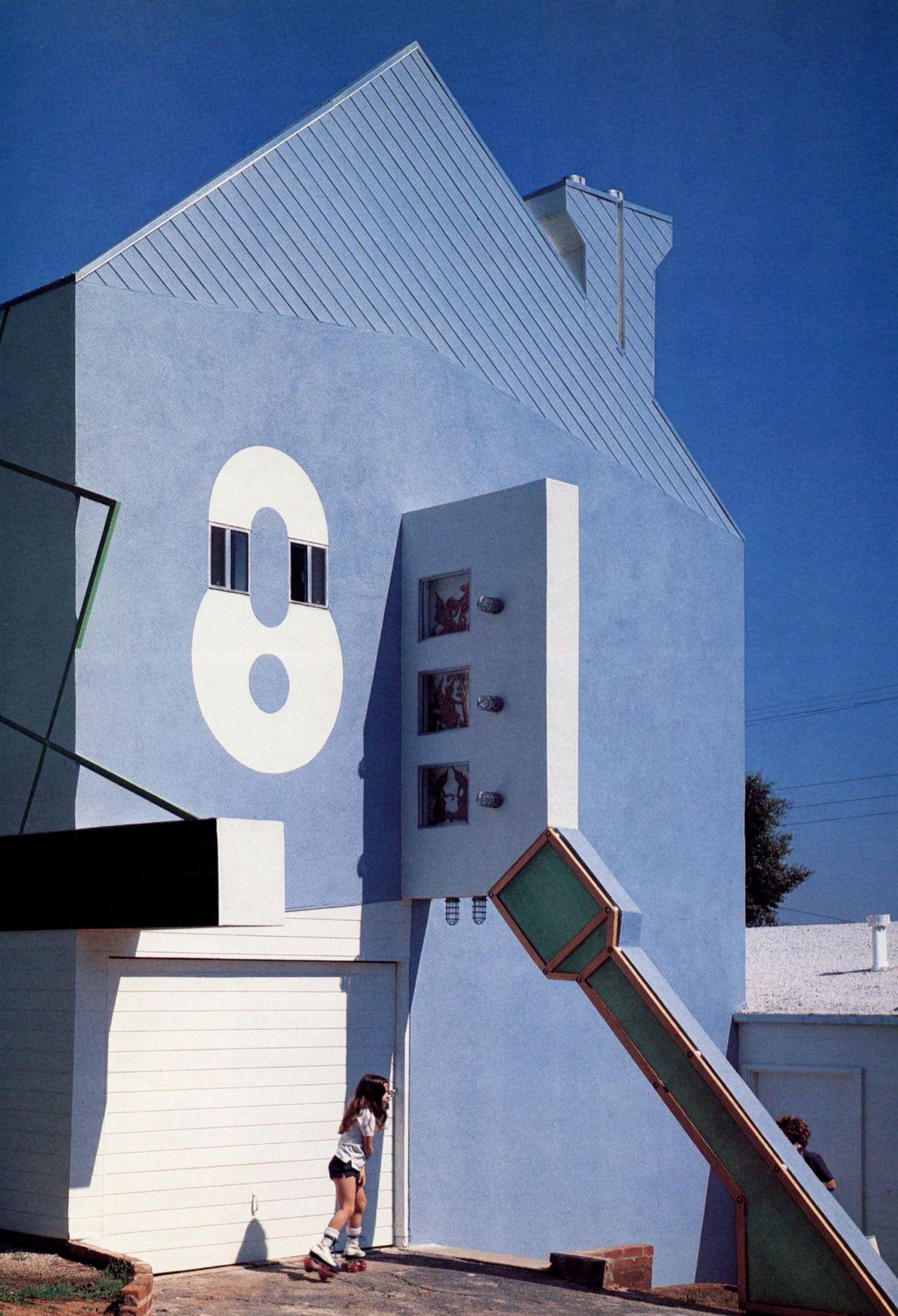

The method outlined here generates a bijective rela- tion between the object depicted (the architecture,

or the city) and its depiction: a relation which produces an interdependence between the two elements. Certainly, the object precedes its depiction, but this does not undermine the equality of this relation. Since color generates a fecund correlation with the spaces of architecture—and, in some way, it “learns” from them—it is not unlikely that (with a little in- version) architecture could learn from color’s features.

Untitled is one of many classical paintings by Mark Rothko (Fig. 5). Painted in 1957, it is on display at the Washington National Gallery of Art. The paint- ing contains three elements, but only two tones. Three different “fields” float against the background. The deep green of the two bigger rectangles clashes with the luminosity of the intense blue strip, which is enhanced by the presence of the darker, less saturated blue.

The painting displays two very simple features. To translate it, one must grasp the following traits. The first is the presence of two surfaces: identical in their character, in the substance which generates them; but different, as a couple of brothers differs from a couple of twins. The second is the presence of the blue, encircling the two surfaces but carrying its own peculiarity. The contour internalizes the two green fields, connecting them through a thinner, lighter strip: the thick frame accepts a smaller gift, whose bright- ening presence underlines—by contrast—the nature of the darker outline.

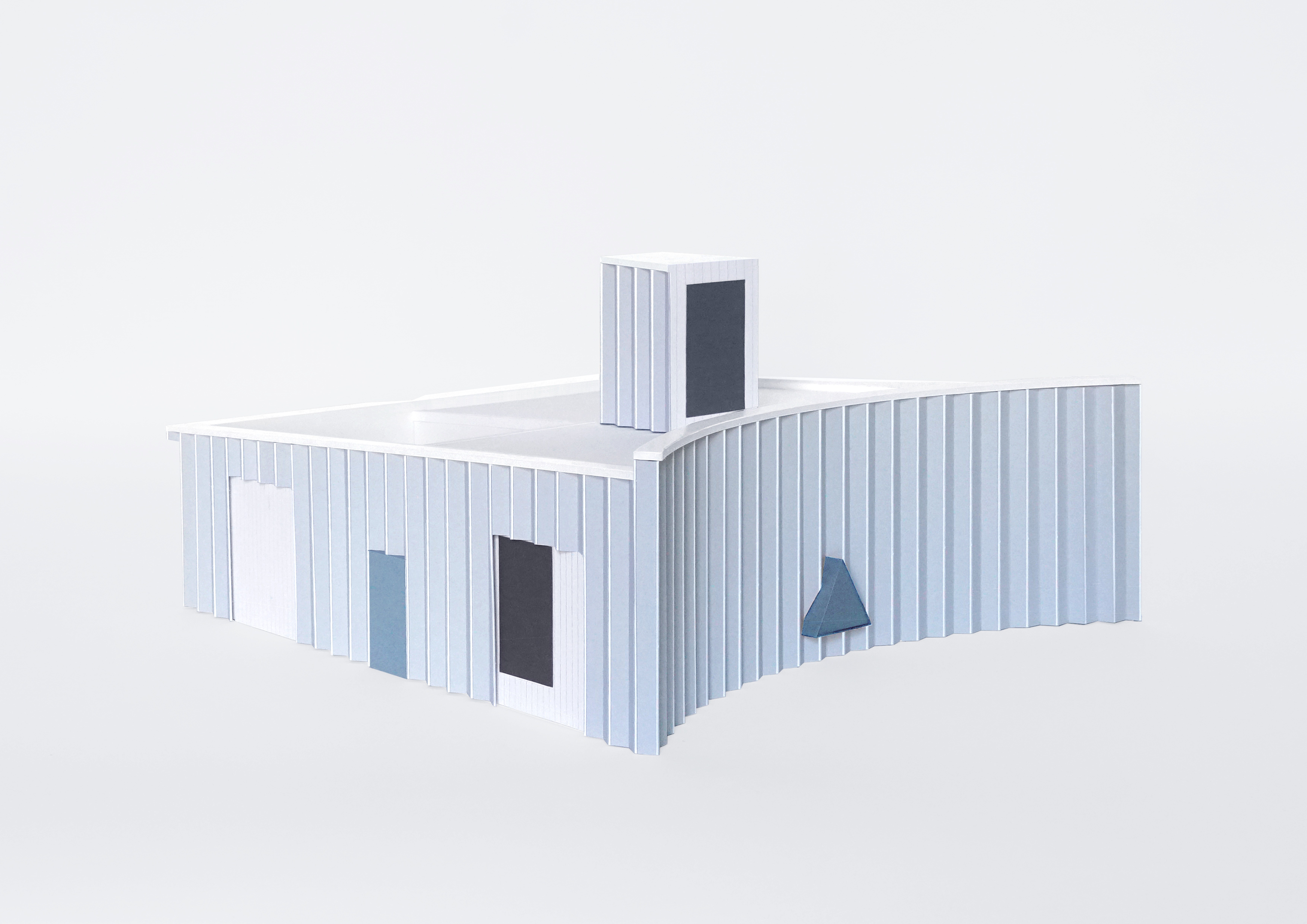

The open-air gallery will, accordingly, consist of two, very simple, features (Fig. 6). The first is the pair of courtyards (Fig. 7), identical in their uncoveredness as well as different. The precise molding of heights and proportions ensures they are equal in their di- versity (Fig. 8, 9). The second is the vestibule. A cov- ered path, a continuous serving space that faces its own variation: a mirrored stairwell giving light to this undivided path, an uninterrupted walkway cutting across the two levels (Fig. 10).

In the year of his death, Itten wrote in his diary: “As a word only related to other words gets her precise sense, colors reach their own distinct expres- sion and their own precise meaning just in relation to other colors.”16

Notes

1 John Berger, Sul disegnare, ed. and trans. by Maria Nadotti (Milano: Il Saggiatore, 2017), 3.

2 Ibid.

3 Vittorio Ugo, “Schema,” XY. Dimensioni Del Disegno, no. 3 (1987): 21–32.

4 Marten Kuilman wisely compares nine “ideal cities” in- spired by Vitruvius and designed in the Renaissance: by Filarete, Fra Giocondo, Girolamo Maggi, Giorgio Vasari, Antonio Lupicini, Daniele Barbaro, Pietro Cattaneo, and Francesco di Giorgio Martini.

5 In this essay, the use of the word “ideogram” is preferred over the sometimes more familiar term “diagram.” While the etymon of the latter means “to write through” and roots its mea ning in the representation of a phenomenon, the word “ideogram” is based on the “writing of the idea,” thus standing for the representation of a concept or principle, more than the depiction of a tangible object.

6 Ugo, “Schema,” 23.

7 Gustav Reinhold Röhricht classified different Jerusalem maps drawn between 1140 and 1321 AD. The so-called Crusader maps are clearly reminiscent of the Isidoran maps: the majority of them follow the model of the round map, and function also as a symbolic representation of the ideal city. In this text, we refer

to the Cambrai map (the older, most distinctive map) and to the Hague and the Uppsala maps (chromatically and formally, these are probably the two most brilliant examples within the group).

8 While all the buildings in Giambattista Nolli’s map are hatched in black, he picks out what he considers to be Rome’s civic places within their floorplan, as if they were open public spaces.

9 Camillo Sitte’s drawings for “The Art of Building Cities” or Allan Jacobs’s same-scale depictions for “Great Streets” are notable examples of this method.

10 One could think, for instance, of the famous 1915 Plan Zuid, drawn by Hendrik Petrus Berlage, or the 1934 Algemeen Uitbreidingsplan, both for the city of Amsterdam.

11 Adolph Gottlieb, Mark Rothko, “A letter from Mark Rothko and Adolph Gottlieb to the Art Editor of the New York Times,” New York Times, June 13, 1943.

12 The word “abstract” and its derivatives come from the Latin abstractus, past participle of the verb abstrahere. The verb, in turn, is an inflection of abstraho, from ab– (away from) and traho (to haul, to pull).

13 Johannes Itten, Arte del colore, trans. by Marta Bignami and Augusta Monferini (Milano: Il Saggiatore, 2022), 11.

14 Ibid., 14.

15 Ibid., 12.

16 Ibid., 8. Cited in his wife Annaliese’s introduction.

Colors

Colors